MEV 101 – The Hidden Cost of Public Mempools

In this module, we explore what MEV is, how it operates in public mempools, and why it has become a systemic problem for blockchain infrastructure. We also look at how MEV distorts incentives, erodes user trust, and has led to the development of mitigation strategies such as MEV-Boost and OFAs (Order Flow Auctions). This foundational understanding sets the stage for the modules that follow, where we will introduce new architectures like SUAVE that aim to create MEV-resistant ecosystems.

Understanding the Nature of MEV

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) is one of the most critical and contentious issues in blockchain ecosystems today. Originally surfaced in Ethereum, MEV refers to the ability of block proposers or other intermediaries to extract additional value from users’ transactions by reordering, inserting, or censoring them. The concept emerged from early arbitrage opportunities in decentralized exchanges, but over time, it has expanded to encompass a wide range of manipulative tactics that undermine user fairness and protocol neutrality.

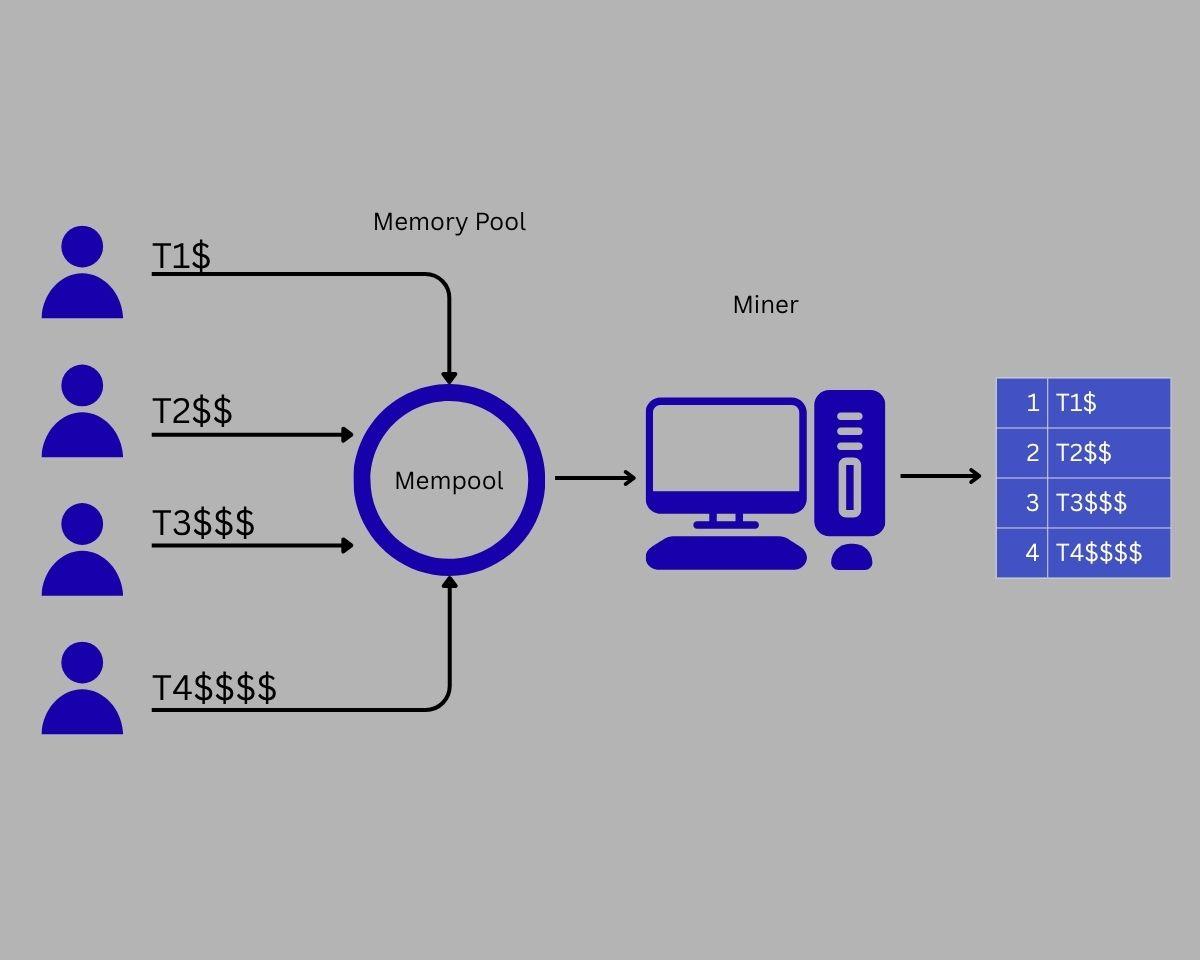

MEV arises from the structure of how transactions are submitted and included in blocks. In most blockchains, users broadcast their transactions to a public mempool—a waiting area where nodes see and propagate these transactions before they are confirmed on-chain. While this approach ensures transparency, it also exposes transactions to strategic behavior by parties who have the power to influence block content and ordering.

For example, when a user places a large swap on a decentralized exchange like Uniswap, that transaction is visible to anyone monitoring the mempool. Sophisticated actors known as searchers can detect the trade, simulate its effect, and then insert their own transactions before and after the user’s in a process known as a sandwich attack. The attacker buys the asset first, benefits from the price impact caused by the user’s trade, and then sells it back at a profit—all at the user’s expense. This is just one type of MEV tactic, but it illustrates the broader issue: visibility plus ordering power enables extractive behavior.

MEV can also take the form of frontrunning, where a searcher replicates a profitable trade and gets it executed first, or backrunning, where the attacker captures residual arbitrage after a known event. Over time, these tactics have become highly automated and competitive, giving rise to a professionalized class of MEV searchers and block builders.

From a Technical Glitch to a Structural Issue

What began as a byproduct of protocol design has evolved into a structural phenomenon. The rise of decentralized finance (DeFi), where hundreds of millions in value are transacted daily through publicly visible transactions, has made MEV an unavoidable feature of the blockchain landscape. Research from Flashbots and other groups has shown that MEV extraction can reach tens of millions of dollars per month on Ethereum alone, with similar activity observed across rollups and other Layer 1 networks.

This level of extraction is not simply a technical curiosity, it has serious consequences for the entire ecosystem. First, it introduces unfairness. Users pay more for execution, face slippage beyond what is expected, and see their intentions used against them. Second, it distorts gas markets. MEV-driven actors are often willing to bid extremely high gas prices to ensure their transactions are prioritized, crowding out regular users and making fees unpredictable. Third, it creates consensus instability. In proof-of-stake networks, validators who can extract MEV are incentivized to centralize block production or collude with searchers, threatening decentralization.

Additionally, MEV leads to wasted blockspace and increased chain reorgs. Searchers may submit duplicate transactions or race multiple versions of the same strategy, bloating mempools and consuming computational resources. In extreme cases, validators may fork the chain or engage in reorgs to capture high-value MEV opportunities, compromising finality and trust in the network.

The Public Mempool as a Vector for Exploitation

At the heart of the MEV issue lies the public mempool. Its openness is both a feature and a vulnerability. While transparency enables users to monitor the network and developers to build tooling, it also gives adversaries an early view into user intentions. Any transaction that appears in the public mempool becomes a signal that can be acted upon before the original transaction is finalized.

This problem is amplified by the latency gap between transaction submission and inclusion. Even in fast blockchains, there is a window, sometimes just milliseconds, other times several seconds—where high-frequency searchers can act on mempool data. Because miners or validators decide which transactions to include and in what order, they become the gatekeepers of MEV. If not regulated or decentralized, this power results in a situation where the block proposer becomes an extractor, not a neutral operator.

Attempts to obfuscate mempool activity, such as by encrypting transaction contents or delaying publication, have had mixed results. While they can reduce some forms of frontrunning, they often introduce latency, break composability, or require additional infrastructure. The underlying problem remains: open systems that rely on public broadcasting are vulnerable to exploitation by parties with faster access, better infrastructure, or privileged block inclusion rights.

MEV Across Chains and Domains

While Ethereum was the original focal point of MEV research, the phenomenon is not confined to any single chain. MEV exists on rollups, Solana, Binance Smart Chain, and even Bitcoin in different forms. The mechanics vary depending on block production, transaction throughput, and smart contract design, but the principle remains the same: ordering rights can be monetized, often at the expense of ordinary users.

In multichain and cross-domain environments, new categories of MEV emerge. Cross-domain MEV involves capturing arbitrage across bridges, Layer 2s, and different decentralized exchanges that are not synchronized. For example, a large mint of a stablecoin on one chain may result in price discrepancies on another chain. Searchers can bridge assets rapidly and profit from the mismatch, often at the cost of users who are slower or unaware of the arbitrage.

Bridging protocols, liquidity aggregators, and oracle updates are all potential sources of MEV. As interoperability increases, so does the surface area for extraction. This makes MEV not just a chain-specific issue, but a network-wide challenge that threatens the fairness and efficiency of the broader crypto economy.

The Need for MEV Resistance

Given its systemic nature, MEV is no longer viewed as a bug to be patched, but a structural problem to be addressed with architectural changes. One approach is mitigation, tools that reduce the worst impacts of MEV without fundamentally changing the infrastructure. These include MEV-Boost, private mempools, and transaction encryption schemes. They offer partial protection but do not eliminate the underlying incentives.

The more ambitious approach is resistance, which is reengineering the block building and order-flow architecture to minimize the scope for MEV. This involves separating block proposal from transaction selection, decentralizing builder power, and introducing competitive auctions for order-flow. In this model, users submit transactions not into a public mempool, but into controlled pipelines where their execution is protected and fairly priced.

MEV resistance is not only about preventing sandwich attacks. It is about aligning incentives across all layers of the blockchain stack, ensuring that validators, builders, and users interact in ways that preserve neutrality, reduce rent extraction, and enhance trust. This vision underpins the development of new architectures such as SUAVE, which will be explored in detail in upcoming modules.